[Note from Christopher: I wrote this short piece on Bill Brett as a sidebar to accompany a longer article entitled “East Texas Cowboin’” by my friend Randy Mallory for the May 2000 issue of Texas Co-op Power Magazine. Bill was a fine man and a wonderful storyteller. He died a couple of years afterward, in August 2002. Upon hearing the news, I wrote a short memorial column for the Beaumont Enterprise newspaper; you’ll find that column in the Newspaper Dispatches section. I still think about Bill. He was a jack of all trades and even ran the little post office in his rural community.]

One time in East Texas, back in the 1980s, at an event that must remain nameless, Bill Brett handed me a small glass jar half filled with clear liquid and said, “Try a swaller.”

One time in East Texas, back in the 1980s, at an event that must remain nameless, Bill Brett handed me a small glass jar half filled with clear liquid and said, “Try a swaller.”

I did. It went down smoother than silk and tasted like fresh water, but when it hit my stomach a warm razzle-dazzle spread outward over my belly, a pleasant gong in B major went off in my brain.

Man oh man, I thought. I couldn’t believe how painless it was to swallow. Not caustic, no fire at all. Handing the Mason jar back to Brett, I commented, with a puzzled expression, “It don’t burn up your throat like that store-bought stuff.”

Brett nodded. “Yep,” he said, “that’s right.” He gave me a wicked grin. “Shore makes you wonder, don’t it?”

It sure did.

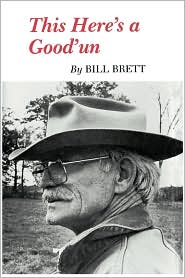

Back in those days I was a newspaper columnist, and in the course of my ramblings I’d met Brett somewhere or other. In his 60s, gray haired and handsome with twinkling blue eyes, he’d impressed me right off as a fella worth knowing. For one thing, he could tell a story. Years later, I saw where The Handbook of Texas, in its section on Texas writers, compares his Bill’s “vernacular narration” to that of Mark Twain. I reckon the Handbook is right, although Brett never used such  words as that, even if he did have a seventh grade education.

words as that, even if he did have a seventh grade education.

He could write a story, too, as I soon learned from reading his The Stolen Steers: A Tale of the Big Thicket and There Ain’t No Such Animal and Other East Texas Tales, both from Texas A&M Press. They’re fine books, and still in print.

Anyhow, as I was saying, Bill Brett impressed me right off. I arranged to drive over to his place in Liberty County, down in the Trinity riverbottom country, so I could sit at his knee, so to speak, and maybe learn a thing or two about telling stories, and about writing some, too. When I drove up in the afternoon, he was out in his yard braiding a horsehair rope. He was wearing boots and jeans and a khaki shirt, had his faithful cowboy hat with a braided horsehair band cocked back.

That was one thing I learned about Brett right away—he sure did like to braid horsehair. Before I left that afternoon, I was wearing a brown and white horsehair band on my own hat. I sat there and watched him make it, too. He had strong sure hands that worked with an economy of motion, the hands of an accomplished craftsman. He also knew how to work with horn. He could take an ordinary cast-off cow’s horn and make it into something worth admiring.

But the thing that struck me most, especially on that first visit, was that Bill Brett was an unusual mixture of woodsman and cowboy. He talked about working horses and cattle, but in the East Texas woods, not on the open prairie. His stories seemed as southern as they did western. They mentioned dark creekbottoms and baygalls and thorny thickets. I’d never heard cowboy stories like that, so I learned something.

Whether I learned anything from him about telling a story, or writing one, is another matter. I’d like to think so, and if he happens to read this, maybe he’ll let me know.

*****